Designing Kiosk Systems

September 28, 2004

by Roy Crisman

Kiosk systems provide a unique set of development conditions and challenges. Whereas most multimedia development produces a software application, a kiosk is a collection of physical, hardware, software and support systems. This article attempts to look at the entire kiosk project, in hopes that you will have control over most of it.

Design the process

You already know to do your Information Architecture (IA), User Interface (UI), and usability design for software before the visual layout and software development. You may even have the time, budget, and foresight to do usability testing focused on your target user base with wire frames on paper or with quick software mockups before starting on graphics and code. But for a kiosk, the product is more than an executable file; it is the entire system and process. Besides creating a simple and intuitive UI, you want to simplify the installation, deployment, and support of your kiosk.

Run the entire process through an IA/UI/usability design phase. Create end-to-end use cases; remember to include service and support personnel as users as well as the end-user. Consider every aspect you are responsible for or interact with. Don't forget computer hardware, peripherals, cabinetry, the Operating System (OS) and third party software, networking, installers, documentation and training manuals, online portions, administration and configuration components, UL-type consumer safety testing and certification, contracts with third party vendors and support systems. If no one considers a component, such as the base system OS, as a part of the end product, no one will be assigned responsibility for it and have time budgeted for it. Parts of your process that fall through the cracks will fall to whoever has the free time or gets stuck with it at the last minute, not the best person for the job.

These initial sketches, charts, and use cases don't have to be incredibly detailed. It is better to realize that these "work products" are just as important to plan, document, and have in source control as the code. Continue to add to them and assign responsibility for the sections as the project grows.

We control the hardware...

Look at the entire scope of the project to determine what platforms(s) you are going to focus on and develop on. It may be helpful to develop for full cross-platform compatibility even if the in-kiosk machine specification is for only one. A cross-platform compliant program can quickly turn into a demo CD-ROM or be viewed by that one client who uses the other platform. You also want to try to keep your options as open as possible to try to limit your risk to hardware going out of production. There are several limiting factors on your hardware selection: certain required hardware components, components without drivers or features for a particular OS, sponsorship arrangements with hardware providers, or required software components such as an ActiveX controller for a digital camera.

Use industrial hardware components whenever possible for parts that the end-user interacts with. Or, use cheap consumer devices with plenty of spares and a quick replacement process. Most consumer keyboards, mice, trackballs, and joysticks weren't made for children to stand on and to have drinks spilled on them daily. I have seen consumer components with impressive technical specs usedÑand replaced after a year's worth of sub-par performance.

With keyboards there are several options:

- On-screen with a touch-screen monitor: This works best for a small amount of data, may be more prone to vandalism and require more frequent cleaning, and have a major impact upon the UI/Usability and visual design.

- Custom industrial keyboard: This is a more expensive option and probably requires a third-party vendor, may require a Quality Control/Quality Assurance cycle of its own, and allows you to define exactly what keys are available to the user.

- Standard keyboard (industrial or consumer): This keyboard already exists, is less expensive and more thoroughly tested than a custom one, and will require some work with the OS to lock out certain keys and key combinations to protect your system.

Choose your industrial hardware supplier and/or physical kiosk fabricator carefully, though. My last kiosk project had a running joke about the vendor's "Don't worry about it, we'll handle it" attitude and inability to complete even simple tasks. They shipped us a new "replacement trackball" that had been removed from service three months previously. The stainless steel kiosk cabinetry arrived on location in a distant city without a hole for power cables to exit. Custom industrial keyboards had their letters rubbed off by use within 6 months.

Just as you may separate generic code and graphics from specific, it can be helpful to keep user-generated data separate from the OS and application. When the OS hard drive becomes physically damaged, you won't lose any of the previous data. You may even separate the OS from the application.

...and we control the software...

The basic kiosk is just an application program (the Show) running in a box. It probably has an "attract loop" which runs between user sessions, and a time-out mechanism which detects when someone has walked off and returns the application to the attract loop.

The Show (and other kiosk applications) should create at least a couple levels of logs. A user-interaction log will record the path the user takes through the application in order to data mine for information about how the kiosk is used. Each component may also have it's own process or debug log to record the progress through the code, the beginning and finishing of functions and methods, relevant variables and states in the case of trapped errors, interactions between components on the kiosk as well as attempts to talk to other machines and network processes. These debug logs are indispensable in solving problems if the kiosk does lockup, crash, or error, or even knowing whether the problem is the code module, the data, the network, or a change to another component having side effects. All log files should be written locally in case off-kiosk communication isn't working and may also be remotely accessed or uploaded to a central location. The data may also be transmitted to a server as it is generated so you can track exactly where a user is, or as part of some multi-user system.

Logging data can be very important for understanding the long-term usage of your kiosks. It also may be important to have archived for historical data: I have parsed through debug logs to discover that the 1.3 release was actually more stable than the 1.2 release-despite client's convictions to the contrary. Version 1.3 was receiving refocused attention due to the upgrade, showing the weakness of relying on anecdotal evidence of kiosk performance.

The Show and kiosk components have a variety of ways to transmit data depending upon your situation: it can be sent immediately via a direct connection, sent as tasks are completed (at the end of a user session), or queued up in batches to be sent only late at night.

Use audio sparingly and wisely. Audio should work with the entire kiosk, not be something someone just throws in at the end. If you do have audio, consider what can be done to make it more tolerable to any people who work around your kiosk installation. There can be quite a lot of intentional damage to your kiosk installation if it aggravates the people who have to work around it. Even during development, it may not be long before someone who sits near the QA machine asks someone to turn off the sound. (A cheap pair of headphones left plugged in to each machine may help ensure office tranquility and allow people to hear the audio when they need to.) Attract loop audio can be especially annoying. Adding randomness and variability to the attract loop audio can greatly increase the experience for people exposed to the kiosk for long periods of time.

Herd animals use deep bass 'lowing' sounds because these can travel over greater distances and are hard for predators to pinpoint the location of. Unless you are creating a kiosk about cows, dinosaurs or the science of sound waves, you should avoid bass, especially when you have a group of kiosks together. This also means you can save money by not buying subwoofer for the kiosk sound system.

One way to reduce the risk of the effect of downtime due to computer errors is a software or hardware "watchdog" component that reboots the machine if the show quits giving it a signal on a regular interval. A hardware version is more reliable than a software solution, because the machine may lockup beyond the ability of the software to restart the system. The watchdog doesn't solve any problems with the kiosk crashing, and any user interacting with the kiosk when it crashes will still have a bad experience, but if the kiosk is automatically back up and running shortly, it may still give many users a good experience. A kiosk that has crashed or locked up (possibly with sensitive user information left onscreen) and sits for hours or days can give a lot of potential users a bad experience.

The kiosk may also require access to configuration settings, utility functions, and the standard OS. It may also be helpful to be able to view logs, turn 'restricted keys' on the keyboard back on, or to re-enable the cursor on a touch screen kiosk for development and testing with a mouse. These configuration components and utilities may also be useful as parts of the Console.

The basic idea of the Console is to be able to control any kiosk from anywhere. Technically proficient on-site support is expensive; design and develop as if you will never be able to have a live human configure or support it again. If programmed well, a configuration application may work on kiosk, on a local console machine, and as a remote console, possibly through a web interface. By making these features usable anywhere, you can change settings or fix problems from around the world or right in front of a suspect kiosk with a wireless device, with the same interface.

The console should be able to make configuration changes to the kiosks, either to a specific kiosk, or broadcast changes to groups of them. It may be useful to be able to control a kiosk by sending it a message that simulates a button push, allowing you to remotely 'drive' the kiosk through a workflow.

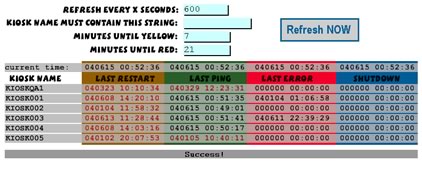

One of the most useful features for your remote console is a "heartbeat monitor." The Show can send a 'heartbeat' of at a regular interval to a remote server, and the heartbeat monitor allows you to view that information. The heartbeat contains a minimal amount of information: Kiosk ID, time and date (if the kiosk is scheduled, otherwise skip it and just use the server's time), and maybe what state the kiosk is in. Some useful states are "StartUp" when the machine reboots, "Error" if an error has been trapped and the kiosk is in an error state, "OK" when the kiosk is running fine, or any other modes or states the kiosk has, such as a "Night" or "Closed" mode, or period of inactivity. The heartbeat monitor then allows to you see what is going on with your kiosks. The minimal heartbeat monitor may just display a green light next to a kiosk name that is ok, a red light next to one that isn't. Without this, you don't have an answer to the question "how are the kiosks doing?". You can also display more information such as state, timestamps for last error, last restart, last OK ping, etc. With this information, you may end up alerting support staff to things such as the network being down, kiosks needing rebooting, or that may something else may be wrong because no has used Kiosk 12 all day.

The heartbeat monitor can also come in handy when running QA tests. Your team can monitor the 10 machines across the hall in the QA lab all day, instead of walking back and forth only a couple of times a day.

The holy grail of modern kiosk development is remote updating. If you never have to physically intervene with a kiosk in order to change the underlying software, you can greatly decrease the cost of bug fixes, content changes, upgrades and updates. The console should be able to schedule remote updates and view versioning information for all the kiosks.

The console application may also be able to create and display other kiosk information, including data-mining information. Any information that can be used to chart user interactions, display usage statistics, orders, purchases, media usage, kiosk uptime or downtime, revenue, etc.

...oh yes, and the Operating System and Supporting Applications...

The creation process of the base OS and the installation of any drivers or supporting application programs is just as important to the success of your kiosk as the kiosk show application. Any third party software required for your kiosk to run should be handled here. This process should be well documented, controlled, and versioned. Small things like the order of installing drivers may be important. Don't upgrade any component without realizing the inherent risk that change can pose. Make changes one-at-a-time with testing, just as you would test major software changes. The more open-ended you can build this process the better. Work to have a single OS recovery package that will adapt and work for variant hardware.

...and the Quality Assurance, too.

Develop on Your Target Platform and Environment

The more restricted the target hardware/OS/supporting application environment is the more important this is. I know... I've got a snazzy laptop and I don't like the "other" platform either. But it only takes a couple of seconds to test a feature or make a screen shot to illustrate a problem on the target platform. And if I can't control that camera with my preferred system or I can't interface with the database because we don't have a network, the development process will take much longer.

Visual designers should also inspect their artwork on the target hardware displays. Graphics look a lot different in a dark cubicle on a perfectly tweaked 21" flat screen monitor than they may on an out-of-box touch screen monitor in a brightly lit room. LCD monitors may have problems displaying high-contrast images. Find out that the black, white and red interface looks like badly compressed jpeg graphics on the kiosk's LCD screen before the client has signed off on the design and all the hardware has been purchased.

Test on Your Target Platform

Independent of your development system, you should have a target platform with controlled and documented hardware, OS and supporting applications.

Test For the Long Term

Most multimedia application programs are run for only a relatively short amount of time in one session and can be recovered by the user if necessary. But tiny memory leaks can add up over 12 or 72 hours, and may be caused by your application, faulty supporting applications or even a specific combination of motherboard, audio-card, video-card and drivers.

Have at least a basic test constantly running on the target platform. I've been known to utilize "RECORDER.EXE" from Windows 3.1 to record primitive user interactions and then loop them for a week. There are much more sophisticated testing programs available. Target a full week of uptime, but build in a daily reboot if your product allows.

You'll also want to have a real QA process. Because you have a narrow target platform, QA can spend their time on the software functionality, rather than testing for compatibility issues. QA should evaluate and verify the entire process, not just the program, whenever possible, from building the OS, adding supporting applications, installing the application, configuring and deploying, and hardware component replacement.

Support

While you may not be actively involved in supporting the kiosk over the full life of its deployment, there are many things that you can do to aid the support of the system.

Keep a backup of the base OS and of the OS plus the kiosk application at hand at any deployment. This can be used to wipe a troublesome machine clean or to format a replacement machine.

Ralph Waldo Emerson said, "A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds", but a reasonable consistency is necessary for kiosks. Imagine trying to fix an upside-down kiosk monitor in a remote location and discovering that two of the screws in the bracket holding the monitor require a star screwdriver bit. Work for consistency. Watch for computer hardware consistencyÑchipsets change in production runs and you never realize the variability in what appears to be the same video card until something doesn't work. Demand consistency from any third party providers.

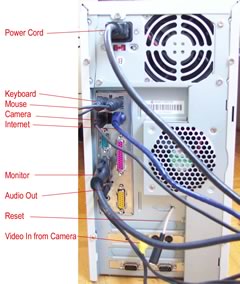

Take pictures of the hardware when it is set up correctly, as an illustration. Take pictures of the finished and deployed kiosks for reference later. It may take a long, long time to figure out remotely that the problem with the kiosk is related to which USB port the digital camera is plugged into.

Take pictures of the hardware when it is set up correctly, as an illustration. Take pictures of the finished and deployed kiosks for reference later. It may take a long, long time to figure out remotely that the problem with the kiosk is related to which USB port the digital camera is plugged into.

Keep an adequate supply of replacement hardware on hand at the deployment site. Hardware seems to fail in pairs, but it may be that hardware failures are only noticed and reported by local staff after multiple units have failed. If you have a bug reporting console component that can be used on-kiosk or on a console machine, you will receive more accurate and helpful data than someone trying to decipher a handwritten log a week later. Remember that local personnel are already fully employed; don't count on adding any task to someone's job, even if it will 'just take a minute'. The security guard doesn't want the added task of shutting down all your machines every night any more than you do. Make sure any contracts and agreements define who is responsible for and who pays for upkeep, cleaning, checking on the physical system (blown monitors) and theft/vandalism.

How hard or easy it is to support your kiosk systems is going to depend upon how well you are able to document, control changes, and simplify systems during development.

Conclusion

Kiosk systems can be rewarding to develop, allowing for far greater control over the system, and the ability to push the limits of multimedia development. A kiosk is so much more than the interface the user interacts with, and thus requires more planning and development than typical multimedia software.

Copyright 1997-2025, Director Online. Article content copyright by respective authors.